To Tom Cotter, the various natural resources his farming operation relies on don’t operate in a vacuum. Rather, they have a relational quality — the role one resource plays in keeping his business viable depends on how it interacts with other resources. For example, rain falling out of the sky is, in itself, a welcome natural phenomenon. But that can change once it hits the ground. Biologically rich soil with plenty of good aggregate structure soaks up that water and stores it for plants to use while growing. But if that soil is too compacted to absorb that moisture, rainfall becomes a source of frustration, or worse, a menace. Cotter, who farms low-lying land near the Cedar River in southern Minnesota, puts it in monetary terms.

“Rich water falls from the sky. Poor water can’t infiltrate, and it makes the soil poorer and your pocketbook poorer,” he says.

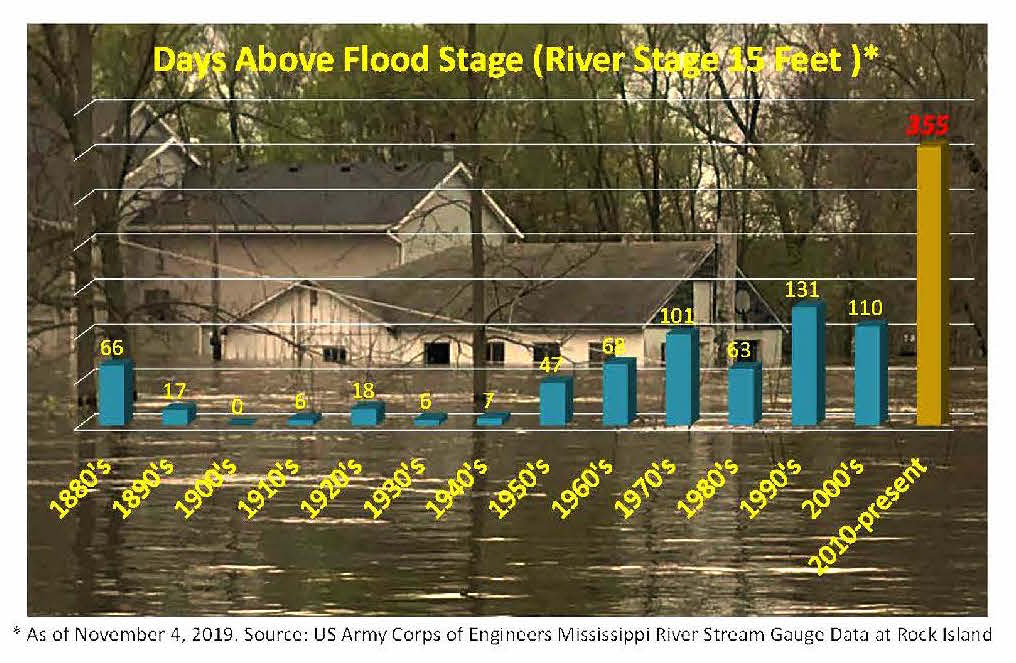

The role “poor water” is playing in leaching profits from fields is a lot on the minds of farmers these days, as climate change produces storms of unprecedented capacity across the landscape. It seems just about every community in the Midwest broke rainfall records in 2019, and a lot of that water pooled up and simply ran off into rivers and streams. Minnesota alone saw its wettest year on record. The Mississippi River was at flood stage deep into the summer. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reports that the volume of water leaving states like Minnesota and flowing downriver through Rock Island, Ill., smashed all previous records. In fact, in Rock Island, the last decade saw three times the number of days over flood stage compared to any decade in the previous 130 years, according to the Corps (see chart below).

A recent study by the First Street Foundation found nearly twice as many properties in the U. S. may be more susceptible to flood damage than government experts had previously thought. Interactive maps developed by researchers show many rural Midwestern counties are much more likely to experience devastating 100-year floods these days. In fact, traditional flooding maps often don’t take into account problems caused by intensive rainstorms, which have become increasingly common as the climate changes.

All that water is washing agrichemicals off farm fields at an unprecedented rate. Monitoring of crop plots at the Olmsted County Soil and Water Conservation District’s Soil Health Farm in southeastern Minnesota shows that as precipitation amounts increased 42 percent from 2017 to 2019, groundwater nitrate concentrations jumped 44 percent. Last fall, scientists recorded an oxygen depleted “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico that was over 6,900 square miles in size, the eighth largest area mapped since 1985. Nitrates and other nutrients escaping farm fields and making their way to the Gulf via the Mississippi are a major cause of the dead zone. Excessive water flow contaminated with chemicals is creating problems closer to home, as well.

Nitrate contamination of drinking water supplies is a growing issue in both private and public systems. According to data from the Minnesota Department of Health analyzed by the Environmental Working Group between 1995 and 2018, tests detected elevated levels of nitrates in the tap water supplies of 115 Minnesota community water systems. In that period, nitrate levels rose in almost two-thirds of those systems. Those water systems serve more than 218,000 Minnesotans, mostly in farming areas in the southeastern, southwestern and central parts of the state.

And all that water is wreaking havoc before it even leaves the farm. A record number of acres in the Corn Belt were never planted — called “prevent plant” — to corn or soybeans in 2019 due to muddy fields. The previous prevent plantings record was set in 2011 at a little less than 10 million acres. In 2019, prevent planting acreage was more than double that. In terms of corn, South Dakota led the country in the amount that wasn’t planted at 2.9 million acres, followed by Illinois and Minnesota at more than 1 million acres each. Stuck equipment was spotted in fields across the Midwest well into the summer, exacerbating soil compaction issues even more.

“Just up the road from me, a sprayer was stuck so badly that an excavator had to come and retrieve it,” says southeastern Minnesota crop farmer Martin Larsen. “And the excavator sank to the cab, so a second excavator and a winch dozer had to come out. You hear about those things happening in peat bogs, but not in the ag fields of Olmsted County. In years like that, it’s not just me that’s questioning whether we can keep farming the way we’ve been farming.”

Managing a Liquid Asset

He’s right. Judging by the turnout at soil health workshops the past few years, an increasing number of farmers are questioning whether production systems that leave the soil uncovered and absent living roots for two-thirds of the year makes sense under this new climate reality. Over two days in late January, a pair of Land Stewardship Project soil health workshops attracted a total of over 200 participants from southeastern Minnesota and northeastern Iowa. The farmers who gathered were there to learn about the economic benefits of building soil health — reduced need for inputs, increased livestock carrying capacity, for example — but also how they could use a solid natural resource to manage a liquid one.

At an LSP Soil Builders’ workshop in Elgin, organizer Doug Nopar noted that in 2019 this particular part of southeastern Minnesota had shattered previous precipitation records by over 10 inches, a situation that’s created a lot of hardship for farmers.

“The bright spot has been farmers getting together and building the knowledge base and skill base to manage these difficulties,” he said.

At the core of this bright spot is the fact that building organic matter in soil using cover crops and managed rotational grazing of perennial pastures not only increases the land’s financial resiliency, but it also has a direct impact on how well it can manage runoff and store moisture. Increasing organic matter levels by 1% can help the top six inches of soil store an extra 20,000 gallons of water per acre, according to one estimate by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Some soil scientists have questioned that figure, saying it can vary based on soil type, for example. But the fact remains: More soil organic matter equals better aggregate structure and thus increased water infiltration and less erosion and runoff.

At the Elgin workshop, Grant and Dawn Breitkreutz described how during the past two decades they have used multi-species cover cropping, no-till, and managed rotational grazing of beef cattle to increase organic matter levels on their fields and pastures, which are a mix of low-lying land and hilly acres along the Minnesota River in southwestern Minnesota’s Redwood County. As a result, their water infiltration capacity has doubled in some cases, and the creeks running through their farm have flat bottoms with gentle, vegetated banks.

“Our soils have room to hold air, water, nutrients,” said Grant. “Our neighbors’ soils are tight and compacted — every tillage pass makes it worse.”

The Breitkreutzes say perhaps the most striking aspect of how they’ve positively impacted their water cycle is that five different springs have emerged on their hillsides. The farmers feel that by retaining water on the high spots of their operation, the moisture is slowly making its way through the soil profile and percolating out in hillside springs. Before, it would run overland quickly, pooling up in low spots at the bottom of the hill, creating boggy areas that were difficult to even graze.

“Now those swamps and bogs that we never were able to graze are pretty regularly productive pastures,” said Grant. “And the neat thing is where these springs are appearing on hillsides, there’s all these different species of forbs and grasses.”

As a result, they’ve quadrupled the livestock carrying capacity on their home farm while slashing input costs.

By increasing organic matter levels in their crop fields, the Breitkreutzes have been able to plant, as well as harvest, their corn and soybean crops on a consistent basis during the past four years “without sinking a combine.”

Grant says 40% of the crop ground in their area wasn’t planted in 2019. And of the acres that were planted, farmers struggled with mud, even on ground that has been artificially drained.

“Our neighbors, you could lay tile lines in the ruts they leave,” he said.

Downstream Thinking

Despite positive changes made to the water cycle on the Breitkreutz farm, there are harsh reminders that we are all downstream from someone else. On July 3, 2018, a 10-inch rainfall in the Redwood Falls area sent water racing from area fields through the Breitkreutzes’ land. During the Elgin workshop, the farmers showed a slide revealing the ugly results: an eroded gully several feet deep slashing through their property.

“You wonder why people downstream from us in agriculture are a little upset? I’m sure that all ended up in Lake Pepin in the Mississippi River,” said Grant.

That’s one reason that during workshops and field days, farmers like the Breitkreutzes are increasingly emphasizing the importance of networking with other producers and working together to get more soil building practices established on a wider swath of the landscape. After all, climate change and the volumes of water it’s producing does not respect property lines.

“This is one of the key benefits,” Dawn said while flashing a slide of a clean, slow-running creek that flows through their farm. “We want to have clean water. We want the people down in Louisiana not to be angry with us anymore.”