Harvey Benson had a simple transition plan for the farm that had been in his family since the late 1860s: he would continue living on those 160 acres until he died, and then it would be passed on to his partner, Bonita Underbakke. In fact, when people ask him if he’s lived on the farm all his life, the 90-year-old quips, “Not yet.” Bonita is 16 years his junior and they have grown quite close since they started dating in 2009 or so. Didn’t this arrangement make sense?

When she learned of this proposal, Bonita, not one to mince words, had a response that was clear and to the point: “That’s not a plan.”

What followed was a half-a-dozen years of discussions, some quite difficult, around creating a more nuanced transition plan for the farm in southeastern Minnesota’s Fillmore County. With the help of a young couple who has an interest in farming, community, and land stewardship, the older couple created an arrangement that strikes a balance of allowing Harvey to live out his wishes without putting an undue burden on Bonita when it comes to estate issues. A bonus is it provides a land access opportunity for beginning farmers while building soil health. It required creative thinking, but Harvey is glad he was pushed to think deeper about the future of the farm — it’s changed not only how he views the land, but how he views himself.

On a spring afternoon, as he gives a tour of the farmstead, Harvey reflects on how he has transitioned from being a “failed farm owner” to someone who is successfully passing on a stewardship legacy.

“I avoided even starting to think about passing on this farm because that would change my relationship with the land,” he says. “But ultimately, I’m very happy with this decision.”

Lifelong Learner

Harvey likes to say that “every decade you learn something more,” and it’s clear his curiosity about the world around him is boundless. He was born in the house he lives in now, and while he was growing up the farm was a typical diversified crop and livestock operation. After graduating from the University of Minnesota, Harvey was a social worker in the area. He eventually moved to Finland, where he taught English at the Helsinki University of Technology for 30 years. After retiring, he traveled around the world for a few years before returning to the farm, where he’s lived for the past two dozen years. During that time, the farm’s been rented to a neighbor who grows corn, soybeans, and alfalfa on the land.

Harvey has no children, and when he entered his 80s, he started thinking more about the future of the land. In 2016, Bonita, a long-time Land Stewardship Project member, talked him into attending a series of Farm Transition workshops the organization puts on periodically. The workshops, which are led by LSP staffer Karen Stettler, offer participants access to legal experts, as well as people who can help retiring farmers and non-operating landowners do the kind of goal setting needed to transition a farm in a way that meets their financial and conservation desires.

Harvey says the workshop was valuable, but he still didn’t feel he was in a position to pass off the farm to the next generation, especially if it meant moving off the land.

Bonita, who is a self-identified “pushy person,” along with Stettler, talked to Harvey about how selling to the highest bidder would likely mean the farm would just become one more field in a bigger cropping operation. Harvey started attending LSP workshops that covered, among other things, building soil health through practices like cover cropping, managed rotational grazing, and no-till. He was intrigued that working farmland could be good for the landscape.

“I’ve got that LSP bumper sticker that says, ‘Let’s Stop Treating Our Soil Like Dirt.’ I look at that every day and think to myself, ‘Good for them,’ ” says Harvey.

And through the Farm Transitions workshop and other LSP meetings, Harvey became aware that beginning farmers face significant barriers when it comes to accessing affordable land.

“Young people, unless they inherit the farm, there’s virtually no way they can get started,” he says. “So I wanted young people with good ideas and who were going to take care of the soil. I wanted people who would be in the community, part of the community.”

Community Couple

Enter Aaron and Amy Bishop. The couple live in nearby Harmony and have roots in the community. Aaron grew up two miles from Harvey’s farm — his family owns and operates Niagara Cave, which offers tours of the underground cavern. He also serves on the local school board, and is involved with other nonprofits. The couple is remodeling an old bank building on the Main Street of Harmony, and plan on turning the upper level into Airbnb lodging and the lower level into space for a future business.

Amy grew vegetables and marketed them through the farmers’ market and Community Supported Agriculture models for four years, and worked at Seed Savers Exchange in nearby Decorah, Iowa, for an additional six. It’s her goal to farm fulltime, and she had been looking for land in the area for a number of years. Both are mindful of land stewardship — Aaron has a geology degree and through his experience studying and exploring southeastern Minnesota’s karst geology, is intimately aware of the oftentimes fraught relationship between land use on the surface and water quality underground.

To top it off, the young couple — he’s 30 and she’s 38 — is close friends with their older counterparts (Harvey and Bonita served as their marriage witnesses). In short, they checked a lot of boxes. “Aaron and Amy are the family Harvey didn’t get around to having earlier,” says Bonita.

There’s just one catch: since they had never anticipated being able to afford 160-acres of land, the Bishops aren’t quite ready to take over management of the entire farm. Timing is the great enemy of successful farm transfers. It’s difficult to align when the landowner is ready to move on with when there is a new farmer ready to step in. But the two couples have come up with ways to manipulate the calendar and fit it to their situation.

Back to the Books

In January, the Bishops officially took over ownership of the farm. However, Harvey will continue to live on the land and call it home for as long as he wants. Even though he’s convinced the young couple’s worldview perfectly matches his values and wishes, Harvey says it’s still difficult to realize he’s no longer the owner.

“Joining futures with them was absolutely the right decision, but it comes with mixed emotions that still rise up once in awhile,” he says.

Because of Harvey’s generosity, the transition resembles a family land transfer more than a sale between two unrelated parties, which made it necessary to make certain the legal details were taken care of to deal with issues like probate law and the “clawback” of assets that can occur if a former landowner needs to go into long-term care. The two couples worked with a local attorney who specializes in ag law; the process required many calls, meetings, and e-mails.

“Harvey was resolute when it came to his expectations of the land transition,” Aaron recalls. “There were multiple ways we could have gone about it, but he wanted no mortgage and no interest involved.”

In order to meet those criteria, the attorney had to delve into notes he’d taken during college classes on seldom-used concepts.

Aaron and Amy will make payments on the farm for 20 years, which will likely cover Harvey’s lifetime; after that, Bonita will receive them. Any payments remaining after Bonita’s passing can be donated to charity. In the end, Harvey will have ended up selling the farm to the younger couple for about half the going market rate.

“Essentially, we will be taking care of Harvey and Bonita until then, with paying off the farm to the agreed-upon amount and time,” says Amy. An unofficial part of this arrangement is that the younger couple will continue doing something they’ve already been doing the past few years: provide Harvey support with maintaining the yard, his house, and his garden.

The purchase agreement includes “a right of reentry” — if Aaron and Amy don’t live up to their promise to keep it a family farm utilizing conservation practices and/or if they don’t allow Harvey to remain living on the property, then the older man, or Bonita, can reclaim ownership.

For Now: Stewards, Not Farmers

The younger couple has also developed a creative work-around when it comes to the other timing issue involved — they may not be ready to farm the land’s 145 tillable acres fulltime, but in the meantime they want to make sure it’s stewarded to Harvey’s specifications. As a result, after consulting the lease templates included in LSP’s Conservation Leases Toolkit, they approached the current renter with three options that provide the opportunity to reduce his rental rate by implementing additional soil-friendly practices — the more cover crops he implements, the lower the rate. The renter recently signed a two-year lease, and for the 2021 growing season went with the middle option offered: planting cover crops on half of the row-cropped acreage.

Amy and Aaron based their rental option calculations on the cost of putting in a cover crop. They also provided the renter resources on cover crop cost-share programs available through agencies like the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Fortunately, Harvey has maintained the fencing on the land, so the renter has the ability to graze his cattle on the cover crops.

“It’s fortunate for us the neighbor is willing and able to continue renting because it’s going to ensure that something’s going to happen under the conservation terms that we worked out,” says Aaron.

The new lease buys the Bishops time to develop and implement various plans for the farm, including returning a portion of it to native prairie. This year, Amy is using three acres on the farm to grow a contracted vegetable seed crop for Seed Savers Exchange and to conduct small grains trials. Meanwhile, Aaron will continue working as a cave guide and substitute teacher.

Harvey is thrilled with this new arrangement. He had previously approached the renter about adopting soil health practices, but the conversations were difficult, with hurt feelings involved. With new owners taking over, it opened up the opportunity to renegotiate the lease without the burden of decades of tradition hanging over their heads. Farm transition experts say that a change in ownership offers a prime opportunity to modify a lease to include more conservation requirements.

Finally, the foursome has come up with a plan to deal with the other bugaboo when it comes to farm transfers: where will everyone live? Harvey has made it clear where he’s residing, and Aaron and Amy will eventually be making their home in a 1950s-era corn crib that is downhill from the house.

After Harvey shows off his tree plantings on this recent spring day, the young couple provide a tour of the crib they are remodeling, pointing out where different rooms and work places will be. They also talk excitedly about future plans for the farm that include the possibility of providing opportunities for other beginning farmers who might want to do everything from rotational grazing to small grains production.

Harvey is excited too. In fact, he asks, why not live a little longer just to see how all these plans work out? “I’m looking forward to this,” he says with a smile.

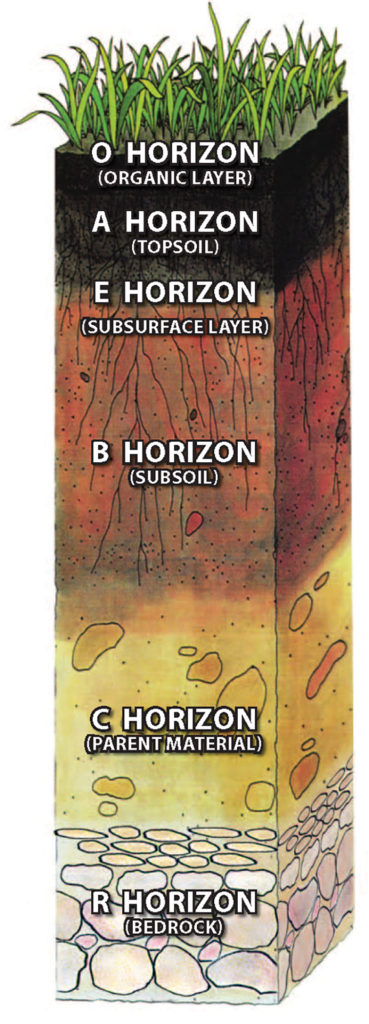

we know as “topsoil,” and it’s full of the living microorganisms and decaying plant roots that create organic carbon. Sitting on top of the topsoil is the “O horizon,” which is made up of dead plants and other organic material in various stages of decomposition. Beneath the A horizon is the subsoil, which normally has less organic matter than the A horizon, so it is generally a paler color. Below that is the “substratum” — a layer of rock and mineral parent material that has not been exposed to much weathering, so is pretty much intact. Finally, in the deepest recesses of the land’s basement is bedrock, or the “R horizon.” All those horizons play a role in making this resource so useful for doing everything from producing food to managing water and storing carbon. But topsoil, despite the fact that it can occupy a relatively narrow space compared to the other horizons, punches above its weight in terms of biological activity. If soil was a car, topsoil would be the gas tank, and without it, that car doesn’t go very far.

we know as “topsoil,” and it’s full of the living microorganisms and decaying plant roots that create organic carbon. Sitting on top of the topsoil is the “O horizon,” which is made up of dead plants and other organic material in various stages of decomposition. Beneath the A horizon is the subsoil, which normally has less organic matter than the A horizon, so it is generally a paler color. Below that is the “substratum” — a layer of rock and mineral parent material that has not been exposed to much weathering, so is pretty much intact. Finally, in the deepest recesses of the land’s basement is bedrock, or the “R horizon.” All those horizons play a role in making this resource so useful for doing everything from producing food to managing water and storing carbon. But topsoil, despite the fact that it can occupy a relatively narrow space compared to the other horizons, punches above its weight in terms of biological activity. If soil was a car, topsoil would be the gas tank, and without it, that car doesn’t go very far.