Ella Robertson and Eric Wana are members of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate and live in northeastern South Dakota. During the past few years, they have been working to reclaim their people’s food producing heritage and show that farming does not have to follow the traditional European model of squared off fields separated from natural habitat. They’re raising traditional fruits, vegetables, and other crops, and are rediscovering the role gathering and preserving “wild” food produced on their reservation can play in providing a healthy form of sustenance. They and other Native Americans are also proving that many of the “regenerative” farming practices spawning so much excitement these days have deep roots in Indigenous ways of interacting with the land.

I recently visited Robertson and Wana to interview them for the We Are Water initiative. Below are excerpts from that interview. You can hear the entire conversation on episode 249 of LSP’s Ear to the Ground podcast.

On a New (Old) Way to Look at Farming

• Robertson: “When it was about fighting the Native Americans of the United States, it was about attacking their food source. So what we’re trying to do is trying to regain that knowledge and strength through our foods, because foods met so much to us.”

• Wana: “The farming that comes to mind to the average person in the United States is a squared, blocked-out piece of land with 40 acres of beans, 40 acres of corn, 40 acres of whatever. Native Americans had agriculture, and it went back hundreds and hundreds of years. We cropped. We had orchards.

“We don’t have 40 acres that we’re growing on. We don’t have 200 acres that we’re planting on. But, that being said, we have what we have here. A lot of the food that we gather is all over our reservation. We harvest from a thousand acres. We harvest from 2,000 acres, throughout the seasons. We’re farmers. Not in the traditional European sense, but we’re farming. We’re actually doing it.”

On Unearthing Indigenous Farming Knowledge

- Robertson: “Talking with the elders about food production, none of them did it. They remember stories, but none of them did it. So last year was the first year we tapped trees and we learned it on YouTube. It doesn’t matter where we learn it from, it’s that we’re trying.”

- Wana: “Before the Internet, I spent a lot of time in the library. Once we got the Internet, oh my god, it opened up a whole new world to me about what my people did, what we did previous to all the hardships endured over the past 150 years.”

- Robertson: “You think about our foods — we had ceremonies, we had songs, we had special prayers that we did for each of those things. And that has gone to sleep. So we’re trying to wake it up. Because to me, that strengthens our connection to Mother Earth. Now that we have a better understanding of that, that’s what we pass on to other people, that’s what we share with our children. Because there is always a reason and a purpose for the way we do things.”

On Why Stewardship of Land & Water is Key to Food Production

- Robertson: “Because we utilize our reservation for collecting, we have to be conscious of what we’re doing, where we’re doing it, and what people are doing on the land. So the bigger picture here is in this smaller area. It’s our reservation, but because we have relatives on other reservations, we have a concern for them. As Native Americans we know we can empathize with those that are having issues with land, with water, with chemical use. You know, because that could be us. It could easily be us. And if we don’t collectively have a concern for it, then nothing can improve, nothing’s going to get better. Water is the center of everything that we do. So when there’s a concern about water, our resources being depleted, then it’s scary for us, it’s a concern for us. Because what we do all centers around water.”

- Wana: “Not too long ago, I wrote a number of papers on drain tiling and the impact it had on our area. So drain tiling has been going on here since the 1880s. Immediately, the impacts were seen amongst our people, because by the turn of the century, those waterways were gone, totally gone from us. A lot of the prairie potholes in the Coteau Areas that originally held water are drained, completely drained. A lot of the lakes, even, were drain tiled out to the point where they wouldn’t flood any more. Seasonal flooding, the refilling of the potholes, it just wouldn’t happen. I mean, there is not a spring in the area, not a lake in the area, that isn’t contaminated in some way, shape, or form.

“So water is life. Water is something from nature that we’re not going to get back from nature once it’s gone.”

And On Passing Knowledge onto the Next Generation

- Wana: “Ella and I are into history, reading books from two or three hundred years ago and accumulating knowledge. When we’re doing these things, writing them down, what’s in the back of my mind is that we’re revitalizing our food ways. Two or three hundred years from now, people are going to be reading about what we’re doing, and the knowledge we’re passing on.”

- Robertson: “I like to say, ‘It’s not lost, it just went to sleep.’ It’s just waiting for us to find it and to breathe life back into it.”

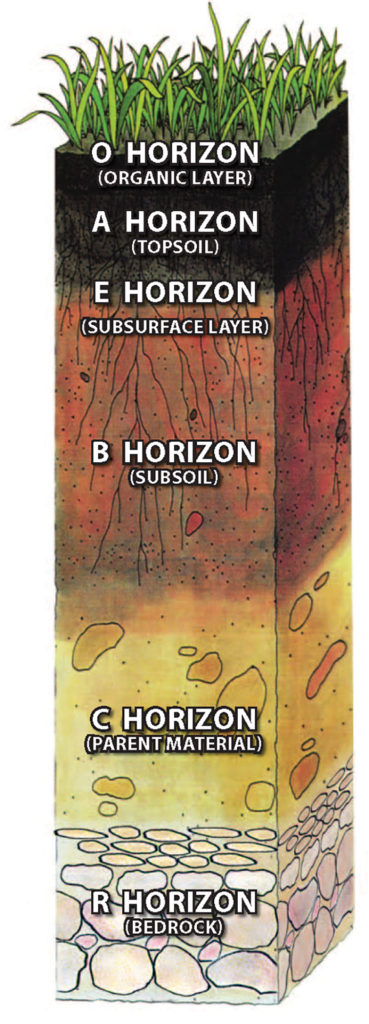

we know as “topsoil,” and it’s full of the living microorganisms and decaying plant roots that create organic carbon. Sitting on top of the topsoil is the “O horizon,” which is made up of dead plants and other organic material in various stages of decomposition. Beneath the A horizon is the subsoil, which normally has less organic matter than the A horizon, so it is generally a paler color. Below that is the “substratum” — a layer of rock and mineral parent material that has not been exposed to much weathering, so is pretty much intact. Finally, in the deepest recesses of the land’s basement is bedrock, or the “R horizon.” All those horizons play a role in making this resource so useful for doing everything from producing food to managing water and storing carbon. But topsoil, despite the fact that it can occupy a relatively narrow space compared to the other horizons, punches above its weight in terms of biological activity. If soil was a car, topsoil would be the gas tank, and without it, that car doesn’t go very far.

we know as “topsoil,” and it’s full of the living microorganisms and decaying plant roots that create organic carbon. Sitting on top of the topsoil is the “O horizon,” which is made up of dead plants and other organic material in various stages of decomposition. Beneath the A horizon is the subsoil, which normally has less organic matter than the A horizon, so it is generally a paler color. Below that is the “substratum” — a layer of rock and mineral parent material that has not been exposed to much weathering, so is pretty much intact. Finally, in the deepest recesses of the land’s basement is bedrock, or the “R horizon.” All those horizons play a role in making this resource so useful for doing everything from producing food to managing water and storing carbon. But topsoil, despite the fact that it can occupy a relatively narrow space compared to the other horizons, punches above its weight in terms of biological activity. If soil was a car, topsoil would be the gas tank, and without it, that car doesn’t go very far.