Building soil health may be about bugs, bacteria, and biology, but justifying farming practices that nurture such a natural process often comes down to a human-generated gauge of success: how much money does it put (or keep) in the bank? On a sunny day in late June, Martin Larsen addresses that question while standing in a 20-acre field planted to oats near the southeastern Minnesota community of Byron. He is hosting an online field day on no-till small grains that’s being sponsored by the Land Stewardship Project and Practical Farmers of Iowa, and one couldn’t have picked a better example of how to add diversity to a corn-soybean rotation. The thigh-high oats are thriving, and Larsen is clearly pleased as he shares aerial drone footage showing acre-after-acre of verdant growth. Over the years, he’s been seeking a viable third crop to diversify his row crop rotation. Larsen has raised a few acres of oats here and there in the past, and the success he’s having this year with this and other fields planted to the crop on a larger scale excites him. These are food-grade oats, meaning there is a good market for the grain. In addition, there is a market for the straw as an erosion-controlling ground cover on construction sites.

Another bonus is that the oats are serving as a nurse crop to a seeding of clover, which will fix nitrogen, further build soil, and serve as a source of forage for livestock.

As his young son, Rudy, plays in the background, Larsen describes the economic benefits of this planting: reduced input costs, multiple markets for the crop, disruption of weed and pest cycles.

“But also remember that the oat crop will give other value,” he adds, going on to make the case for future financials. “Of course, there’s the soil health benefit.”

Over time, small grain rotations diversify the soil biome with their dense root structure, building the kind of organic matter that reduces the need for purchased fertilizer. Indeed, research and on-farm experience is increasingly showing that when small grains like oats or rye are rotated into a row crop system, corn and soybean yields increase.

“So when we look at the financials of oats, look ahead and look at the whole systems approach,” Larsen says. The farmer also encourages the online audience to consider another benefit of building soil health with a rotation that gets more roots in the ground more months of the year. Toward the end of his presentation, he flashes a slide showing how much nitrate-nitrogen was discharged from tile drainage outlets in the area thus far in the 2020 growing season. Nitrogen is a key corn fertilizer, and keeping it from escaping fields and making its way into ground and surface water is a major challenge in places like southeastern Minnesota.

The chart shows that the corn and soybean ground that’s had cover crops integrated into it is consistently producing nitrate-nitrogen runoff well below 10 parts per million, the Environmental Protection Agency’s safe drinking water standard. But a line in the graphic tracking nitrogen loss in a cornfield that’s not had the benefits of cover crops or a small grains rotation rises higher and higher as the growing season progresses, finally peaking at around 12 or 13 parts per million in early June.

“That cover crop was really able to hold that nitrate concentration down,” Larsen says. “This is just a slide about other things I’m passionate about, and reasons I’m doing this.”

As he hints at, Martin Larsen is passionate about a lot of things: agronomy, conservation, geology, hydrology, farming, and, perhaps most interesting of them all, cave exploration; Larsen spends up to 500 hours a year crawling around in Minnesota’s underground wilderness.

But as this recent field day makes clear, the place where all these passions converge is rooted in the soil itself. As a result, during the past few years Larsen has become a point of connection himself. Through his various explorations below and above ground, he’s helping farmers and non-farmers see the positive role agriculture can play in creating a healthier landscape that is economically and ecologically more resilient.

Beneath the Roots

“The science connected to water, and then it connected to farming, and then it connected to caving,” says Larsen of why he got involved with caving around seven years ago. Not coincidentally, it was at about that time he started using no-till and cover cropping techniques on the 700 acres of land he farms.

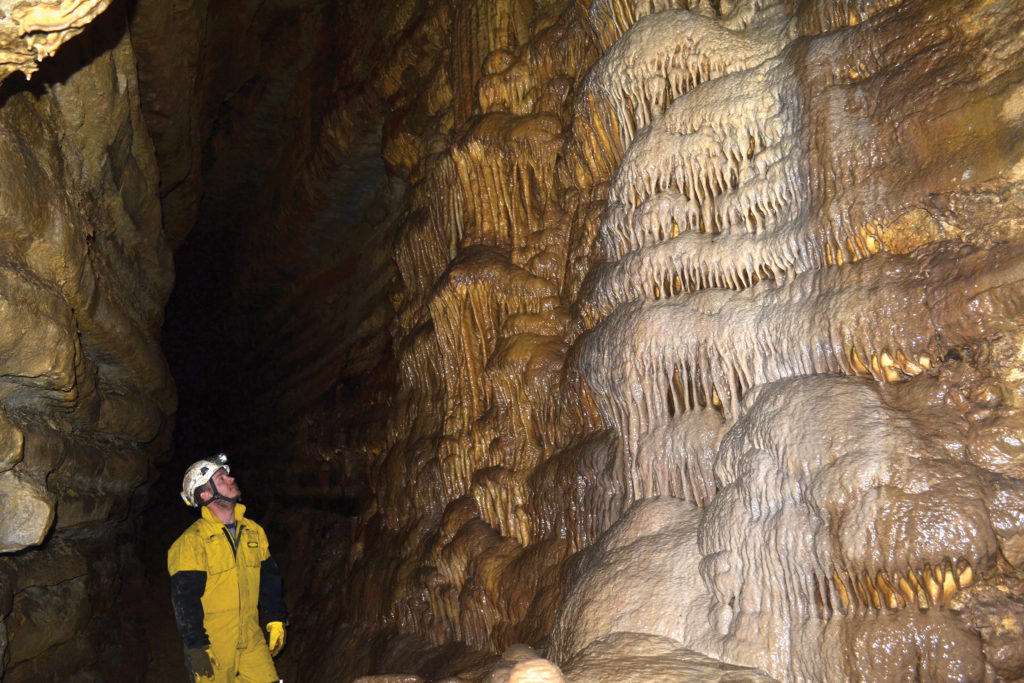

As Larsen explains these linkages, he’s scrambling around in the dark of southeastern Minnesota’s Spring Valley Caverns, a five-mile-plus labyrinth of claustrophobic passages and crawl spaces, rooms with vaulted ceilings, and pits that drop to dark depths. He trains his headlamp at water dripping from a cave ceiling and explains that just a few days ago this moisture may have been precipitation that had fallen onto a hayfield 45 vertical feet from this spot. It’s a striking reminder of just how dynamic the Swiss cheese-like limestone karst geology that dominates this region is.

Spend any time with the fifth-generation farmer, especially in a cavern, and it becomes clear that caving isn’t just a hobby — it’s a thrilling way to make direct connections between land use on the surface and water quality below. He describes being in caverns so shallow that the rumble of a county road could be heard overhead; other times he has rappelled into pits that have their true depth obscured by water pooled at the bottom. Larsen likes to show a photo at presentations of a well pipe emerging from a cave ceiling—a graphic indication of the intimate connection between the land’s surface and our aquifers. In the age of Google Earth, exploring unmapped regions is increasingly less of an option. But Larsen has found a way to push into the unknown very close to home.

“The thrill of caving is to find an unexplored new passage. When you are the person that is first entering that passage, your light is the very first light, and your eyes are the very first eyes to ever see that passage,” Larsen says excitedly as he makes his way through the narrow passageways of Spring Valley Caverns like some sort of subterranean rock climber. “You’re exposing yourself to a certain level of risk, doing things that we as humans aren’t really meant to do. It’s really an eye opener to a part of Minnesota that truly very few of us have seen.”

Sometimes what one sees and experiences isn’t always pleasant, or safe.

Larsen and other cavers in southeastern Minnesota and northeastern Iowa have had to fight their way through mountains of foam created by liquid manure and other organic pollutants. They have experienced cave floors that resembled, as Larsen calls them, “satanic slip and slides” because of all the eroded, muddy soil covering them.

He has also taken samples of cave drips that show nitrate levels well above drinking water standards. That’s a concern, given that in southeastern Minnesota, the majority of drinking water is drawn from what’s flowing through these caverns and the rest of the karst geology that makes up this hollow land. And climate change has altered the volume and timing of water moving through the system. Larsen and his caving companions have had a few close calls where massive storms filled caverns to the ceiling soon after they had emerged from underground.

Like any adventurer, Larsen has a high tolerance for discomfort, like the time he was rappelling down a pit that had never been explored and ended up in a place where “bodies aren’t supposed to be.” After being stopped by water, he started to ascend, and ended up getting stuck in a crevice.

“It took me one inch at a time to get up and out of that crevice, for over an hour,” recalls Larsen. “There’s nothing normal about it.”

In a way, Larsen says, caving isn’t unlike researching and implementing farming techniques that create economic and environmental resiliency on the surface. There are rewards, as well as risks, involved with regenerative agriculture.

On Larsen’s own farm, cover cropping and no-till have helped build his soil’s health, reducing erosion while breaking up weed and pest cycles, and thus reducing his reliance on chemicals. Water is infiltrating the soil better, an important consideration at a time when climate change is inundating fields with extreme rainfall events.

Larsen’s day jobs on the surface world put him in a position to have a positive impact on the quality and quantity of water making its way through the karst in torrents and trickles. Besides being a farmer, Larsen is a feedlot technician for the Olmsted County Soil and Water Conservation District. He is also a member of the Land Stewardship Project’s Soil Builders’ Network, which is bringing hundreds of farmers from around the region together around building healthier soil in a financially viable way.

Farmers, scientists, environmentalists, and soil health experts say Larsen’s ability to combine his firsthand observations and practical experience with the latest research is a significant resource, and a model that should be replicated throughout the state.

“Every county should have two or three of him,” says Jeff Green, a Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) groundwater hydrologist who works with Larsen. “I don’t know how you describe Martin — a hydraulic Renaissance Man? I’m not quite sure. He does caving, which is exploration, learning more. But he’s also taking that information and getting people to make changes with it.”

Dark Business

Larsen got interested in caving partly as a result of dye tracing work he was doing with Green. This kind of research consists of dropping fluorescent dyes into sinkholes or “blind valleys”—areas where perennial streams drop out of sight and continue their journey underground—to determine groundwater movement. Green and other hydrologists have used this technique to gather extensive data on karst groundwater, creating, for example, one of the most extensive springshed maps in the country. But from the time that dye enters the ground to the time it exits in a spring or well — sometimes hours, days, months, or even a year later — there is a mysterious period where a lot is unknown about its movements.

Larsen feels caving can help him fill in some missing puzzle pieces when it comes to the movement of water. He and other cavers in the area have worked with hydrologists at the DNR and the University of Minnesota to help track water movement. They have also worked with Larry Edwards, an internationally known geochemist who has done cutting edge work on using water-formed cave formations to gauge changes in the climate over the millennia.

Larsen has a business degree from Winona State University and admits to not paying much attention in geology class. But he has a natural scientific curiosity and a drive to learn more about the relationship between the natural environment and farming, as well as other land uses. There are times when his thrill-seeking, ability to put up with physical discomfort, and scientific curiosity intersect, like the time he and some companions spent 16 hours in Tyson Creek Cave crawling on their stomachs through water in a passageway that was never more that 24 inches high. After two-thirds of a mile, they came to a spot where the water was flowing in two directions.

“This is the first time to my knowledge that we have ever discovered this in the state of Minnesota, where we actually encountered a place in a cave where you physically can look at the water choosing two different paths, and likely, two different springsheds,” says Larsen.

A Messenger to the Surface World

When it comes to karst and groundwater quality, Larsen, and others, have some bad news. As more land has been converted from perennial systems like hay and pasture to annual row crops like corn and soybeans, nitrate levels in groundwater have gone up. The Environmental Working Group has released an analysis of public records showing that one in eight Minnesotans are drinking nitrate-tainted tap water. Hastings, Minn., had to spend $5 million on a reverse osmosis system that can take nitrates out of the water, and other communities have had to abandon wells that were polluted by fertilizer runoff.

Not only is a crop like corn reliant on nitrogen fertilizer, but annual row crops like corn and soybeans only cover the land around a third of the year, leaving bare soil vulnerable to leaking nutrients and other contaminants into groundwater. Couple that with a changing climate that is producing extreme rainfalls more often, and it’s a recipe for disaster.

“That’s showing up in more than one location—that we’re getting an increase in volume of water and concentration of pollutants,” says Larsen. “So it’s pumping the room full of gas, and now with climate change, you’re igniting it.”

Research at the Olmsted County Soil and Water Conservation District Soil Health Farm shows that as precipitation amounts increased 42 percent from 2017 to 2019, nitrate concentrations in the water beneath the root zone of the crops growing in the plots increased 44 percent.

To top it off, water can infiltrate karst rock in some surprising ways, making its way through pores too small to see with the naked eye. In Spring Valley Caverns, Larsen shines his headlamp on the ceiling of a low, narrow passage. The rock appears to be an impenetrable mass, but it’s weeping water like a rung-out sponge.

Larsen says what troubles him the most is that widely accepted “best managed practices,” also known as BMPS, don’t seem to be addressing the problem adequately.

“We know now that even with the right rate, the right amount, and the right timing, we’re not getting water that’s drinkable below our row crops,” he says of BMPs such as highly calibrated applications of fertilizer and precision planting. “And as a farmer, that really speaks to me. We need to do something better than status quo.”

The good news is Larsen is part of a growing group of farmers in the region who are going beyond the status quo and building the soil’s ability to hang on to nitrates and other nutrients before they make it into cracks, crevices, joints, and eventually, our aquifers. One soil building method that is showing particular promise is integrating covers crops like small grains and brassicas into corn and soybean systems. Studies across the country show that cover cropping not only dramatically reduces erosion and surface runoff, but builds the soil’s ability to better manage water and nutrients by increasing organic matter. Having living roots in the soil year-round is a key to creating fields that are more resilient, particularly under extreme weather conditions.

Larsen is certainly proving that on the land he farms. He’s also excited about research he and others recently conducted at the Olmsted County Soil Health Farm showing the positive impacts of cover cropping. Plots grown without cover crops had nitrate concentrations in the water escaping the root zone of 13.14 parts per million. Cover cropping reduced those levels to 8.84 parts per million.

The DNR’s Green says it’s key that people like Larsen can offer farmers a comprehensive look at ways they can protect groundwater. Sinkholes may be the most evident, and dramatic, threat to aquifers in karst country. Manure, pesticides, bacteria, and even pharmaceuticals can make their way through these gaping holes, especially during intense rain events.

But day-in and day-out, the biggest threat to karst groundwater is nitrate runoff from farm fields. And it often takes a more indirect, hard-to-control route—down through the soil profile. In fact, groundwater research at Big Spring in northeastern Iowa shows that the vast majority of the nitrate contamination is coming from water carrying it through the soil column and into the bedrock.

When Ron Pagel was growing up on his family’s farm near Eyota in southeastern Minnesota, he was always mindful of the threat direct runoff posed to water in the area. There was a spring that was some 300 feet away from an area near the barn where they wintered cattle. Not only did runoff from the feedlot threaten to make it into the spring, but also a stream that runs through the farm and eventually empties into the Root River.

“It was no secret where heavy rains were going from that feedlot,” says Pagel. Today, the farmer — he has a small dairy and a cow-calf beef herd, along with 434 acres of crops — has a manure storage unit in place to not only keep that waste out of the water, but to create a situation where he can collect the manure and use it as a source of soil-building fertility. Pagel credits Larsen for helping him through the process.

As a feedlot technician, Larsen helped with the engineering, as well with getting state, county, and federal cost-share funds to help with construction. That’s important, particularly when prices for commodities like milk are in the dumps.

But just as importantly, Larsen has helped farmers like Pagel control the indirect runoff that trickles down through the karst. Pagel’s family has been planting cover crops for the past half-dozen-years. Not only do the covers contribute to soil health, but they serve as a cheap source of grazing forage for his cattle.

“All my land has either hay on it or cover crops this year,” says Pagel proudly. “Especially when you look at the forecast or watch the rain gauge fill up, like it seems to a lot these days, it’s nice to know you have the land covered, soaking it up.”

Pagel and other farmers who work with Larsen say it’s key that he not only knows how water behaves beneath the surface, but also speaks the language of economics. Larsen formerly worked in agronomy sales, and knows that farmers, especially these days, are constantly having to mind their bottom line. He also knows the power of communicating clearly and in an engaging manner about the agronomic benefits of building soil health.

For example, Larsen likes to tell the story of Bear Spring, which flows out of the ground not too far from where he farms. During a 24-hour period in June 2018, 1,520 pounds of nitrogen was discharged from the spring, according to water monitoring. Larsen calculates $35 worth of nitrogen fertilizer was being flushed out of that spring per hour. Now, multiply that by the thousands of springs that are present in southeastern Minnesota alone.

“Money is coming out of that spring,” he says. “And it’s a lot because it doesn’t stop.”

All of a sudden, the $30 per-acre investment a farmer might make when planting cover crops looks pretty good.

Having someone who can communicate about the big-picture, long-term benefits of building soil health is key to expanding practices like cover cropping and managed rotational grazing in the region, says Shona Snater, who co-directs LSP’s Soil Builders’ Network. People like Larsen are a critical link in helping farmers transition from trying a new practice to actually making it a routine part of their operations. That’s especially important when a farmer enters the second or third year of a new practice, and runs into problems.

“They can come to an event and learn how to get started, but if they don’t have a support group or technical support, someone who they can turn to when problems come up, then they aren’t going to be able to maintain that practice in the long-term,” Snater says.

Larsen’s twin messages about the vulnerability of our groundwater and proactive steps we can take to protect it can resonate beyond the farming community. Deirdre Flesche once saw the farmer give a presentation on karst geology and soil health during an LSP event at Niagara Cave, a commercial cavern near Harmony, Minn. She came away alarmed and energized.

“I was shocked that he could smell manure in the caves,” says Flesche, who serves on the Lake City Environmental Commission, which advises officials in that community on issues like energy conservation.

After seeing Larsen’s presentation, Flesche began working to get the Commission to address water quality concerns as well. She feels farmers as well as non-farmers must be more aware of how quickly and dramatically their land use decisions on everything from fields to lawns can impact the groundwater.

“If we’re going to be able to protect the water supply, we need to be aware of how this water moves through the karst,” she says. “I don’t think people have a clue how vulnerable our water is.”

Larsen is working hard to provide some of those clues, and to show that he and other farmers can offer a viable alternative.

Pushing Beyond the Unknown

Part of the allure of caving is to constantly push further. What’s beyond that hole full of soil and rubble? Is that air whistling through a crack a harbinger of a huge gallery bristling with stalactites and stalagmites?

Innovative farming involves pushing for more as well. Larsen, an obsessive tinkerer, has built a planter that will allow him to better interseed cover crops in his corn before harvest, giving them a jump-start before winter. He posted pictures of the tricked-out seeder on his Facebook page and was flooded with questions and comments from other farmers who are working to find creative ways to build healthier, more resilient soil.

Whoever he’s talking to, Larsen is willing to admit that when he started changing the way he farmed, he was nervous and made (and is still making) mistakes. But his passion for groping around in the dark and seeing firsthand how land use above impacts water quality below gave him an extra incentive to get past that initial trial-and-error stage. To him, the stakes are too high to do otherwise.

“The scarring of the farming landscape really troubles me, so it’s pushed me to change the way that I farm. That’s our mentality, as humans and as farmers, to adapt, to learn the new way to do it that works better,” he says. “We can talk about what happens in the cave. We can talk about what happens in the water. But we have to get back to accountability to our farms and to our soils, and to keeping them viable.”